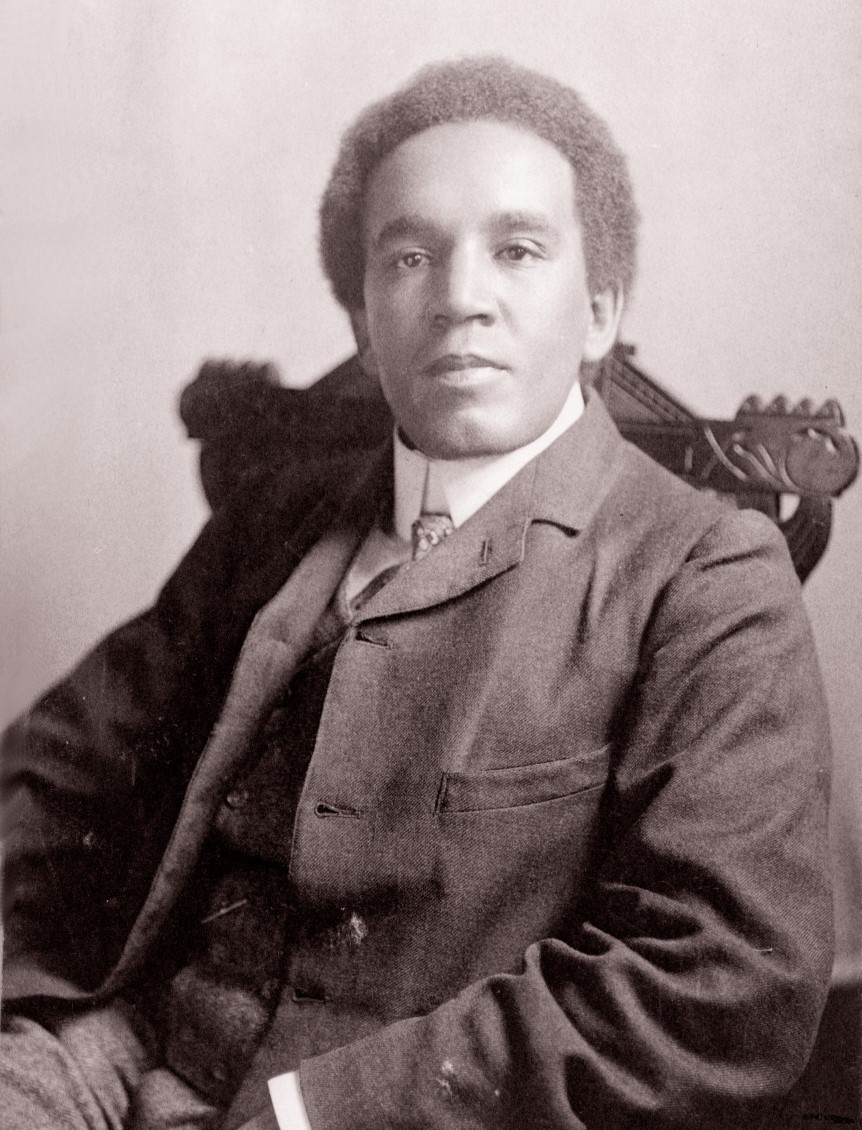

Samuel Coleridge Taylor [1875 - 1912]

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor was born in 1875 in London to Alice Hare Martin (1856–1953), an English woman, and Daniel Peter Hughes Taylor, a returnee Krio man from Sierra Leone who had studied medicine in the capital. He became a prominent administrator in West Africa. After Daniel Taylor returned to Africa without learning that Alice was pregnant, Alice Martin named her son Samuel Coleridge Taylor after the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Alice lived with her father Benjamin Holmans and his family after she had her baby. The family lived in Croydon, Surrey. In 1887 Alice Martin married George Evans, a railway worker. Taylor was brought up in Croydon. There were numerous musicians on his mother's side and his grandfather played the violin and taught it to Taylor who went onto study at the Royal College of Music, beginning at the age of 15. He changed from violin to composition, working under Professor Charles Villiers Stanford. After completing his degree, Taylor became a professional musician, soon being appointed a professor at the Crystal Palace School of Music; and conducting the orchestra at the Croydon Conservatoire.

In 1899 Coleridge-Taylor married Jessie Walmisley, whom he had met as a fellow student at the Royal College of Music. Six years older than him, Jessie had left the college in 1893. Her parents objected to the marriage because Taylor was of mixed-race parentage, but relented and attended the wedding. The couple had a son, named Hiawatha (1900–1980) after a Native American immortalized in poetry, and a daughter Gwendolyn Avril (1903–1998). Both had careers in music: Hiawatha adapted his father's works.[9] Gwendolyn started composing music early in life, and also became a conductor-composer; she used the professional name of Avril Coleridge-Taylor.

By 1896, Coleridge-Taylor was already earning a reputation as a composer and made three tours of the United States, where he participated as the youngest delegate at the 1900 First Pan-African Conference held in London, and met leading Americans through this connection, including poet Paul Laurence Dunbar and scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois. Having met the African-American poet Paul Laurence Dunbar in London, Taylor set some of his poems to music. A joint recital between Taylor and Dunbar was arranged in London, under the patronage of US Ambassador John Milton Hay. It was organised by Henry Francis Downing, an African-American playwright and London resident.

Coleridge-Taylor was 37 when he died of pneumonia. His death is often attributed to the stress of his financial situation. He was buried in Bandon Hill Cemetery, Wallington, Surrey (today in the London Borough of Sutton). He was survived by his wife Jessie (1869–1962), their daughter Avril and son Hiawatha.

A yearlong Festival commemoration of Croydon’s composer, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, ended with the unveiling of a plaque on the house where he died on September 1st, 1912: 6 St Leonards Rd, Waddon, formally known as Aldwick.

Speeches were made by Stephen Harrow, the Festival Committee Chair, Jonathan Butcher, the Festival’s Artistic Director, and the conductor, Kenneth Alwyn, who has had an illustrious career conducting the Royal Ballet during the time of Fonteyn and Nureyev, winning a Gramophone award for best film music,

After the unveiling it was onto the Old Town Youth Club for a lunch reception, more talks and a performance of Songs of Sun and Shade sung by Jonathan Butcher. Jeff Green, the composer’s most recent biographer, gave his thoughts as to what kind of music Coleridge Taylor might have written had he lived longer into the 20th Century. Former Royal College of Music Professor, Oliver Davies

Talking about his personal role in building up the RCM Coleridge-Taylor archive, and his friendship with the composer’s son Hiawatha and daughter Avril.

See also report on Inside Croydon: http://insidecroydon.com/2013/01/02/conductor-alwyn-unveils-blue-plaque-to-croydon-composer.

JONATHAN BUTCHER’S SPEECH AT PLAQUE UNVEILING

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor lived here - at 6 St. Leonards Road, formally known as Aldwick, for the last few years of his all too short life. He and his family had apparently moved here from their previous home, Hillcrest on the London Road in Norbury, because it was too noisy for his composing. Incidentally - it was at Hillcrest, now demolished, that SC-T composed Thelma, his only large-scale opera of which we, Surrey Opera, gave the World Première at the start of this, the Centenary year of his death.

It is said that Aldwick was C-T’s favourite house as it was quiet and, more or less, in the country. It’s hard to believe this now, but back then there was a good number of fields, including I suspect one immediately behind the house, where the Parish Church Junior School now stands. There were no extra houses squeezed in here and there, in fact you were in the country. SC-T would take walks into the lanes around here, reading poetry and visiting the villages of Beddington and the like. Yes – rural Croydon.

A Croydon Resident Coleridge-Taylor spent his entire life, apart from infancy, living in the environs of Croydon. There’s no record of him ever suggests leaving the area. C-T, and later with his wife and two children, lived in at least 11 different houses in the Croydon area.

They say, don’t they, that getting married, divorced or moving can be some of the most stressful things to cope with in life, so can you imagine what it must have been like for Coleridge-Taylor with his gruelling schedule of rehearsing, teaching, conducting, adjudicating and, of course, there’s that little matter of composing. Hiawatha, his son, was said to be a noisy child so despite the rural surroundings, the house was perhaps not quite as quiet as C-T would have liked. However, there was a fairly easy solution – build a shed in the garden – the famous Music Shed, which stood there – ‘though as I typed this out a couple of days ago it struck me that that couldn’t have been quite the perfect solution?

What if it was winter or just a bit chilly outside? Even with a good old-fashioned paraffin fuelled valour stove it must have been pretty difficult to keep a garden shed warm! Incidentally - the Music Shed may still exist:

Gwendolyn/Avril Coleridge-Taylor, C-T’s daughter, tried at one stage to sell or give it to the Royal College of Music. Understandably, they turned it down.

Where on earth would they house a garden shed?

Anyway - somehow SC-T kept composing to the end and one thing I find quite extraordinary is that he appears to have left no substantial unfinished manuscripts, like so many before him. Only a few sketches exist, which are at the RCM, so nothing for future generations of musicologists, composers or arrangers with which to fiddle! A Tale of Old Japan Here at Aldwick Coleridge-Taylor scored his last choral work A Tale of Old Japan, which I am pleased to say has been performed in Croydon during the Centenary year by the Croydon Bach Choir, though regrettably their finances did not run to an orchestral accompaniment.

Curiously - in C-T’s wife’s memoirs of her husband, she says that he preferred A Tale of Old Japan to Hiawatha and felt it might be equally successful, particularly financially! He wasn’t going to sell it to Novello & Company for just 15 guineas outright this time! The text is by Alfred Noyes, who less than a 3 year after the work’s first performance, at the old Queen’s Hall, London, was to write a poetic eulogy to the composer for his elaborate head stone. The story goes that not only was SC-T not asked to conduct the first performance, but he had to buy his own tickets - for himself, his wife Jesse and their two esteemed guests – Mr & Mrs Herbert Beerbohm Tree no less! Some reports suggest that this latest incident happened at the now demolished Grand Theatre in Croydon not so far from here, when a local Croydon choir mounted a further performance of A Tale of Old Japan. I like to think that this is a Croydon story – the Queen’s Hall have enough of it’s own anyway.

The Violin Concerto Also composed at Aldwick was the Violin Concerto – there’s so much to be said about this amazing work that I’ll just say that it’s second version did not go down with the Titanic, that there is a manuscript score of the first version, based round a couple of Negro melodies in the Royal College of Music’s archives and the third and final version C-T, more or less, wrote out from memory, when he knew that version 2 had been lost in transit. Some of you may have heard Samuel Staples’ wonderful performance of the Concerto on the 15th December at our Gala Concert, and so I hope you are convinced of its fine quality. Hiawatha Ballet Other works composed here were the set of Hiawatha ballet pieces, later to be orchestrated by Percy E. Fletcher and a number of songs including, rather spookily, one entitled Life & Death! And that’s it – there didn’t appear to be anything else in the pipeline, although there must have been any number of compositional projects going around in C-T’s head.

He was never short of ideas or inspiration, but somehow during the summer of 1912 he had just a little time on his hands, so much so that Jessie, his wife, commented ‘oh go and write a Benedictus.’ He didn’t, but a few days before he died he went for a walk with Gwenie, his darling daughter - apparently he was in good health – he bought a bunch of chrysanthemums, returned home and presented them to his wife. ‘Though C-T was famously known to have been an exceptionally kind and gentle person this gesture of appreciation was, we understand, somewhat out of character. Jessie was a little perplexed!

After presenting his wife with her bouquet Coleridge-Taylor decided on a trip to Crystal Palace – the Disney Land of the day - to view an exhibition of Chinese pottery that he had heard about. Sadly - he was to get no further than West Croydon Station, where he collapsed. The musical world at large mourned that sad loss and Croydon turned out in force to salute and remember their fellow Croydonian. In fact, so much so that St. Michael and All Angels, where the funeral took place, could not house the overflowing congregation and the roads were lined four deep as the funeral cortege made it’s way to Bandon Hill Cemetery. Had medical help been more advanced in those days he might have made a recovery, but the fact that SC-T was such a heavy smoker couldn’t have helped his illness. He apparently composed mainly standing up at his upright piano in the Music Shed with a pen or pencil in one hand and a cigarette in the other - or close by.

After his collapse he did manage to stagger out of the station and take a tram back home, but by then the pneumonia, that was to take his life, had clearly already taken hold and four days later Samuel Coleridge-Taylor died at ten past six on Sunday 1st September 1912. In those last few days, as he lay upstairs here in his feverish state Coleridge Taylor insisted on checking through the orchestral parts of his Violin Concerto, which had recently been sent back from the US and the work’s World Première by the American virtuoso Maude Powell, for whom the work was commissioned. The parts were complete and they were ready for the British Autumn premiere under Henry Wood. Coleridge-Taylor was not to witness that 2nd performance, though it is said that in his last hours he seemed to be conducting an imaginary orchestra in the slow movement of the Concerto. Could there be anything more appropriate.

English and Black Heritage Despite Samuel Coleridge-Taylor being of mixed race – as I am sure you all know by now his father, whom he never knew was from Sierra Leone – he wanted to be remembered as an English composer. Yes, he acknowledged and celebrated his black heritage, he was a member of the Pan African movement in London and arranged numerous African songs and dances – most notably his 24 Transcriptions of Negro Melodies - but when you listen to his own individual compositions, his influence is more that of the American Indians, Longfellow’s Hiawatha with, of course, a considerable nod to his beloved Dvorak. Although SC-T was not by any means the only black man to be seen in and around Croydon at the turn of the 20th Century he would have been noticed, my mother’s piano teacher knew the great man who lived at one stage on the same road. I would like to think some who passed SC-T in the street might have remarked ‘that’s Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, our composer.’ One Hit Wonder? Certain composers have been unkindly referred to as ‘one hit wonders’ despite the obvious brilliance of their one major work. That cannot be said of SC-T. Yes, Hiawatha’s Wedding Feast is glorious and was an instant and international success, but I believe despite its success and it’s obvious knock on effect of bringing it’s composer even more into the public eye and ear, Hiawatha, in some ways, eclipsed much of Coleridge Taylor’s other work. SC-T became a super star on his own merits – no agents or publicists to give him a leg up. Just think about the Variations for ‘Cello and Piano, the early orchestral song "Zara’s Earrings", "the Nonet", The Fantasievstucke for String Quartet, the Clarinet Quintet, the Violin Concerto, the Symphony, the Symphonic Variations on an African Air, The Bamboula, Thelma – the list goes on. All these works are substantial and excellent and that’s before we start to list the huge and varied output of songs, instrumental music and the church repertoire. It’s frankly astonishing and mind-boggling. When did he find the time to write all these? More Than Just The Hiawatha Man!

So - in conclusion and before we actually unveil the plaque I must say that this has been an extraordinary year. More so than I would have thought possible. Before I embarked on this wonderful SC-T journey I am ashamed to say I knew little about ‘Croydon’s composer.’ As many of you will know I soon became utterly absorbed and sometimes overwhelmed by the man and his music. I have met and made friends with some fascinating people, all of whom have been generous with their time and talents. This is not the moment for thanking people, but I must say that this year would not have been remotely possible if it were not for the enormous contribution from so many kind and gifted people. Samuel Coleridge-Taylor’s music is worth hearing. Hiawatha may have overshadowed so many of his other compositions, his style and sound world may have harked back to a bygone era, his early death and the intervention of the 1st World War may have allowed people to forget him too quickly, but one thing is absolutely certain Samuel Coleridge-Taylor is up there with the best of them not least his fellow students at the RCM – Vaughan Williams, Holst, Ireland, Delius etc. He was a genius, definitely, but oh so much more than just the Hiawatha Man!

For more about Samuel Coleridge Taylor click on the link below

https://sites.google.com/site/samuelcoleridgetaylornetwork

Location: Aldwick, 6 St Leonards Road Waddon, Croydon, CR0 4BN